Introduction to Cultural Movements

The 15th century was a crucible of change, a period when the foundations of the medieval world began to crumble, paving the way for a new era of intellectual ferment and artistic innovation. While the Italian Renaissance bloomed with classical revival and artistic mastery, a distinct, equally transformative movement was taking root north of the Alps: the Northern Renaissance. This vibrant period, characterized by its focus on religious reform, empirical observation, and a more pragmatic humanism, did not emerge in a vacuum. Its very essence was shaped, accelerated, and profoundly amplified by one of history's most pivotal technological innovations: Johannes Gutenberg's movable-type printing press.

Before the Press: A World of Scarcity

For centuries prior to Gutenberg's invention around 1440, the creation and dissemination of knowledge was a laborious and costly endeavor. Books were hand-copied by scribes, primarily in monastic scriptoriums, a process that was slow, prone to error, and incredibly expensive. A single book could take months or even years to complete, making them luxury items accessible only to the wealthiest elites, the Church, and a handful of universities. Knowledge was therefore concentrated, controlled, and scarce, limiting literacy to a privileged few and hindering the rapid exchange of ideas across vast distances.

Gutenberg's Revolution: The Dawn of Mass Communication

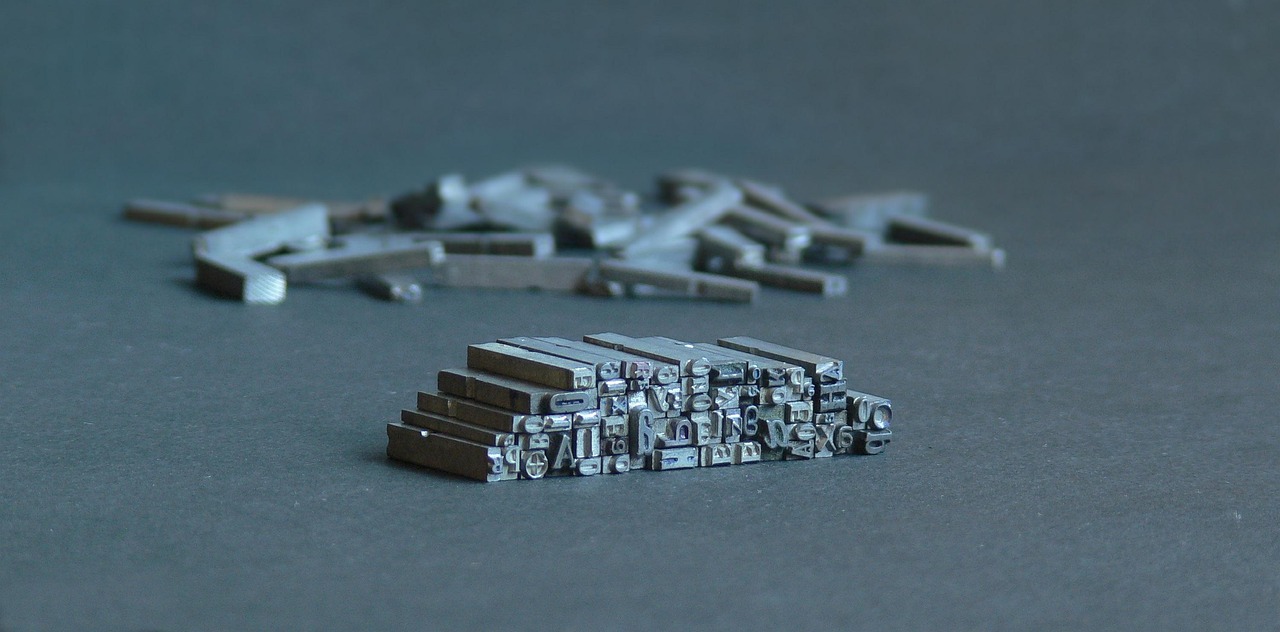

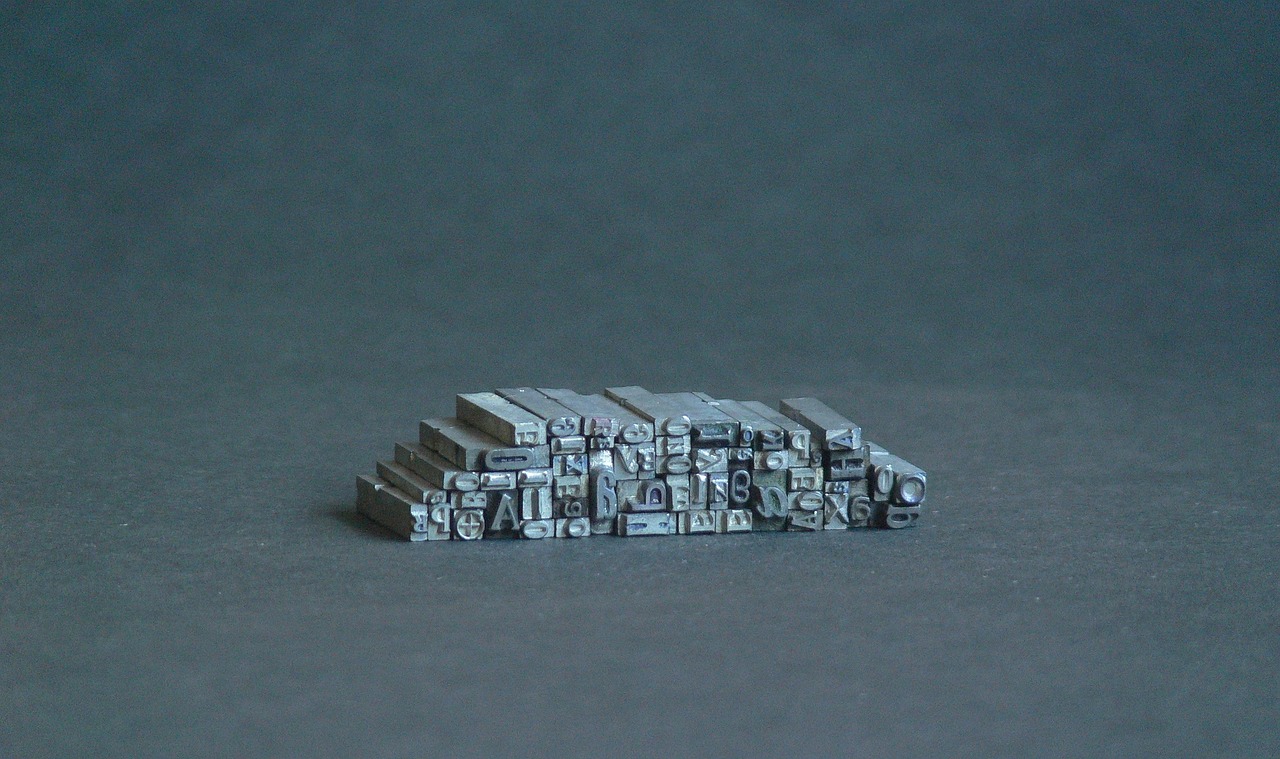

Johannes Gutenberg, a German goldsmith from Mainz, forever altered this landscape. His ingenious system of movable metal type, combined with oil-based ink and a modified wine press, allowed for the rapid, standardized, and relatively inexpensive production of texts. The first major work to emerge from his press, the magnificent Gutenberg Bible, was a testament to the quality and potential of this new technology. Suddenly, what once took a team of scribes years could be accomplished in a fraction of the time, producing multiple identical copies with unprecedented accuracy.

The Echo Spreads: Dissemination and Democratization of Knowledge

The impact was immediate and profound. Within decades, printing presses proliferated across Europe, from Mainz to Venice, Paris, London, and the Low Countries. The cost of books plummeted, making them affordable for a broader segment of society. This democratization of knowledge had a ripple effect, stimulating literacy rates and fostering an insatiable demand for printed materials. The shift from Latin, the language of scholars, to vernacular languages in published works further widened access, allowing common people to engage with texts in their native tongues.

Catalyzing the Northern Renaissance: A Multifaceted Transformation

I. Religious Transformation: The Reformation's Engine

Perhaps nowhere was the printing press's impact more evident than in the religious upheavals of the 16th century. Martin Luther's Ninety-five Theses, famously nailed to the church door in Wittenberg in 1517, would have remained a localized academic dispute without the printing press. Instead, copies of his arguments, along with his German translation of the Bible, spread like wildfire across Europe. For the first time, individuals could read and interpret scripture for themselves, challenging the Church's monopoly on religious authority. The press became the primary weapon in the propaganda wars of the Reformation, disseminating theological treatises, pamphlets, and caricatures that fueled both Protestant and Catholic movements.

II. Humanism and Scholarship Reborn

The Northern Renaissance humanists, unlike their Italian counterparts who often focused on classical aesthetics, applied humanist principles to reform Christianity and society. Figures like Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam utilized the printing press to produce critical editions of classical texts and, most significantly, a new Greek edition of the New Testament. This allowed scholars to scrutinize the original biblical texts, leading to new interpretations and a deeper understanding of early Christian thought. The press facilitated the creation of intellectual networks, allowing scholars to share ideas, critique one another's work, and build upon previous discoveries at an unprecedented pace.

III. Scientific Advancement and Exploration

Before the printing press, scientific knowledge was often fragmented and inconsistent due to errors in hand-copied manuscripts. The press enabled the standardization of scientific texts, diagrams, and maps. Andreas Vesalius's groundbreaking anatomical atlas, De humani corporis fabrica (1543), with its accurate and detailed illustrations, could be widely distributed, transforming medical education. Nicolaus Copernicus's heliocentric theory, though controversial, found its audience through printed books. The reliable dissemination of scientific observations and theories accelerated the pace of discovery and facilitated collaboration among natural philosophers, laying the groundwork for the Scientific Revolution.

IV. Art, Literature, and Education for the Masses

The printing press also democratized art and literature. Woodcuts and engravings could be mass-produced, making art accessible to a wider public and influencing artists like Albrecht Dürer. Instruction manuals for various crafts and trades became available, fostering skill development. Furthermore, the availability of affordable textbooks fueled the growth of schools and universities, expanding educational opportunities beyond the traditional elite. Popular literature, including ballads, plays, and moral tales, found a vast new audience, contributing to the development of national languages and literary traditions.

V. Political and Social Impact

Beyond religion and scholarship, the printing press had profound political and social ramifications. It fostered the rise of public opinion, as political pamphlets and news broadsides circulated widely, enabling citizens to engage with current events. Governments utilized the press to issue laws, decrees, and propaganda, while dissidents used it to challenge authority. By facilitating the spread of shared ideas and vernacular languages, the printing press also played a crucial role in the formation of national identities, laying the groundwork for modern nation-states.

Conclusion: A Lasting Legacy

Gutenberg's echo reverberated throughout Europe, fundamentally altering the course of the Northern Renaissance. It was not merely a tool for reproducing texts; it was an engine of change that dismantled monopolies on knowledge, ignited religious reform, spurred scientific inquiry, and empowered individual thought. The printing press didn't just disseminate existing ideas; it catalyzed the creation of new ones, fostered critical thinking, and reshaped the very fabric of society. Its invention marked the true beginning of the information age, laying an irreversible foundation for the modern world and ensuring that the intellectual and cultural dynamism of the Northern Renaissance would leave an indelible mark on history.