Introduction to Scientific Discoveries

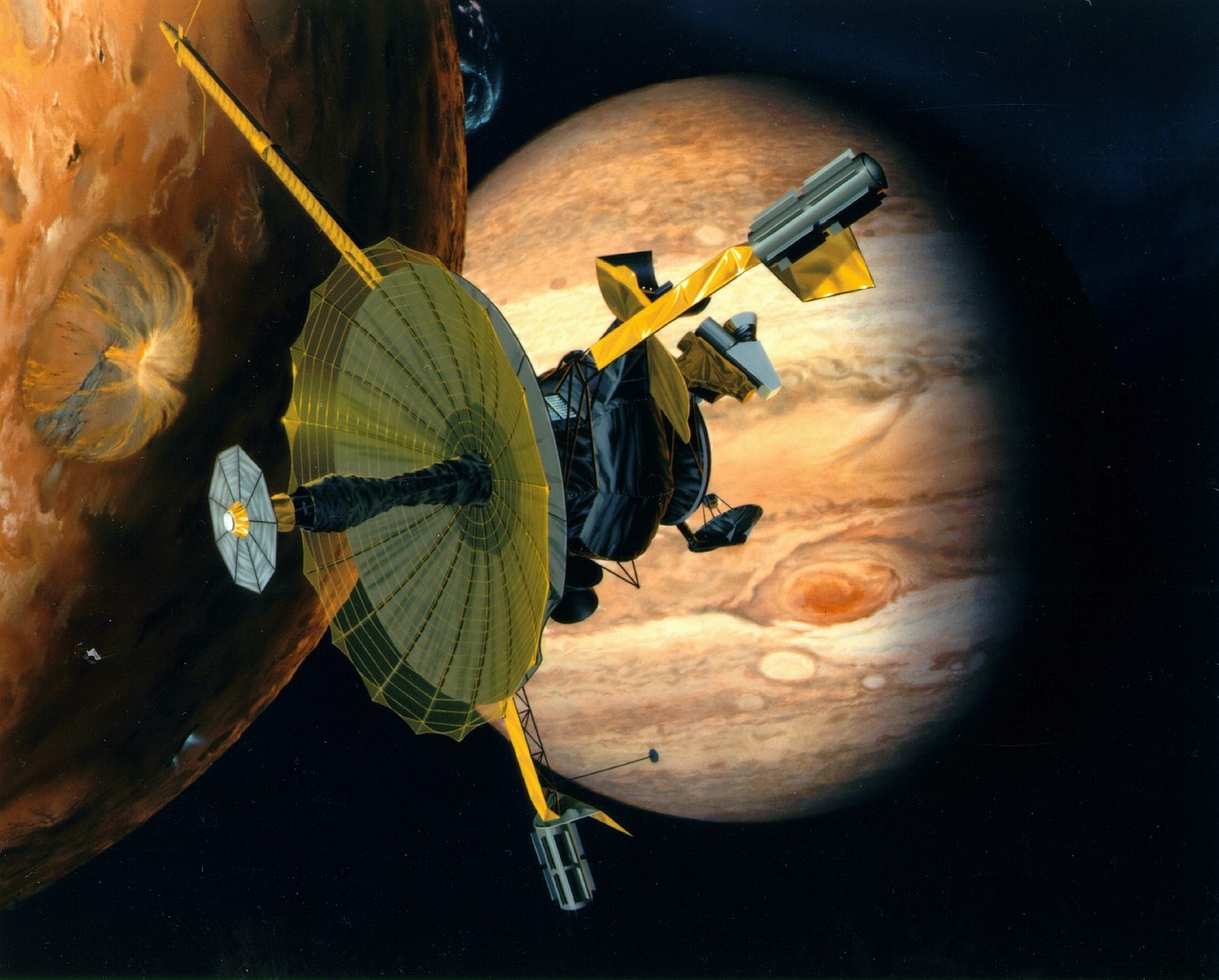

In the quiet solitude of his study, under the vast, star-peppered canvas of the early 17th-century Italian sky, Galileo Galilei aimed his crude, self-made telescope at the heavens. What he saw through that rudimentary lens would not only redefine humanity's understanding of the cosmos but also ignite a firestorm of controversy that would echo through centuries, forever linking his name with both scientific triumph and tragic persecution. The seemingly simple observation of four tiny points of light dancing around Jupiter became a pivotal moment in history, a direct challenge to millennia of entrenched dogma and the very foundation of the universe as understood by the Church.

The World Before Galileo: A Geocentric Universe

For over 1,400 years, the Ptolemaic system, an intricate geocentric model of the universe, had reigned supreme. Earth, stationary and unmoving, lay at the center of creation, a divine stage around which the Sun, Moon, planets, and fixed stars dutifully orbited in perfect crystalline spheres. This model, deeply interwoven with Aristotelian philosophy and reinforced by Christian theology, placed humanity at the apex of God's design, a cosmic privilege that was both comforting and seemingly immutable. To suggest otherwise was not merely a scientific disagreement; it was an affront to divine order.

Galileo's Innovation: The Eye to the Heavens

While not the inventor of the telescope, Galileo significantly improved its design and, crucially, was among the first to systematically turn it skyward. In the autumn of 1609, he began his celestial observations, revealing wonders previously unseen: the craggy surface of the Moon, the myriad stars of the Milky Way, and the phases of Venus, which offered early hints of a Sun-centered system. But it was his observations of Jupiter in January 1610 that provided the most direct and devastating blow to the geocentric worldview.

The Celestial Revelation: Jupiter's Dancing Stars

On the evening of January 7, 1610, Galileo observed Jupiter and noticed three small, bright "stars" aligned near it. He initially dismissed them as background stars. However, over the next few nights, he continued his observations, meticulously charting their positions. To his astonishment, these "stars" were not fixed. They moved relative to Jupiter, sometimes appearing on one side, sometimes on the other, changing their configuration each night. By January 13, he identified a fourth "star."

The implications were staggering. These were not background stars but rather bodies orbiting Jupiter itself. He initially called them the "Medicean Stars" in honor of his patron, Cosimo II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany. Today, we know them as Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto – the Galilean moons.

A Cosmic Paradigm Shift: The Earth is Not Alone

The discovery of Jupiter's moons was revolutionary for several profound reasons:

- Challenging the Geocentric Model: The Ptolemaic system posited that all celestial bodies orbited the Earth. Galileo's discovery proved this unequivocally false. Here were four celestial bodies clearly orbiting another planet, not Earth. This demonstrated that there could be multiple centers of motion in the universe, severely undermining the uniqueness and centrality of Earth.

- Refuting Aristotelian Physics: Aristotle's cosmology held that celestial bodies were perfect, immutable spheres moving in perfect circles. The existence of moons orbiting another planet suggested a more complex, dynamic universe, and later observations of lunar craters and sunspots further eroded the idea of celestial perfection.

- Providing Evidence for the Heliocentric Model: While not direct proof of Earth orbiting the Sun, the Medicean Stars offered a powerful analogue. If Jupiter could have moons, why couldn't Earth? It made the Copernican model, where planets orbited the Sun, far more plausible by demonstrating that not everything revolved around our planet.

The Gathering Storm: Science vs. Dogma

Galileo published his findings in March 1610 in a short treatise titled Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger). The book was an instant sensation, but its implications were deeply unsettling to the established order. While some astronomers and scholars embraced his findings, others, clinging to traditional views, either dismissed them as optical illusions or outright fabrications. The most significant resistance, however, came from the Catholic Church.

The Church, having adopted the Ptolemaic system as consistent with biblical interpretations (e.g., Joshua 10:12-13, which implies the Sun moves), viewed the heliocentric model as heretical. If Earth was not the center, then humanity's special place in creation was questioned. If the Bible could be wrong about the cosmos, what else could be questioned?

The Trial and Enduring Legacy

The conflict escalated over the next two decades. Despite initial support from some high-ranking Church officials, Galileo's unwavering advocacy for the Copernican system, culminating in his 1632 work Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, led to his infamous trial by the Roman Inquisition in 1633. Found "vehemently suspect of heresy," he was forced to recant his views and spent the remainder of his life under house arrest.

Yet, the truth, once seen, could not be unseen. Galileo's observations, particularly of Jupiter's moons, provided empirical evidence that shattered an ancient paradigm. His work, alongside that of Copernicus and Kepler, laid the groundwork for Isaac Newton's universal law of gravitation and ushered in the Scientific Revolution. The Medicean Stars, those tiny specks of light dancing around Jupiter, became a powerful symbol of scientific inquiry, demonstrating that observation and evidence, not dogma, were the true arbiters of cosmic truth. Galileo's "heresy" was, in fact, a profound step towards enlightenment, forever expanding humanity's view of its place in the grand, dynamic cosmos.